Carma

Available On: Steam

Released: 03/06/2021

Role: Producer & Team Lead

Available On: Steam

Released: 03/06/2021

Role: Producer & Team Lead

Out drive your friends in fast, arcade-style vehicle combat, using power-ups, killstreaks, and the environment to smash your foes! Battle across a miniature world, avoiding dangers and earning the gods favour to level up and unlock a wide range of customisables to help you stand out from the crowd.

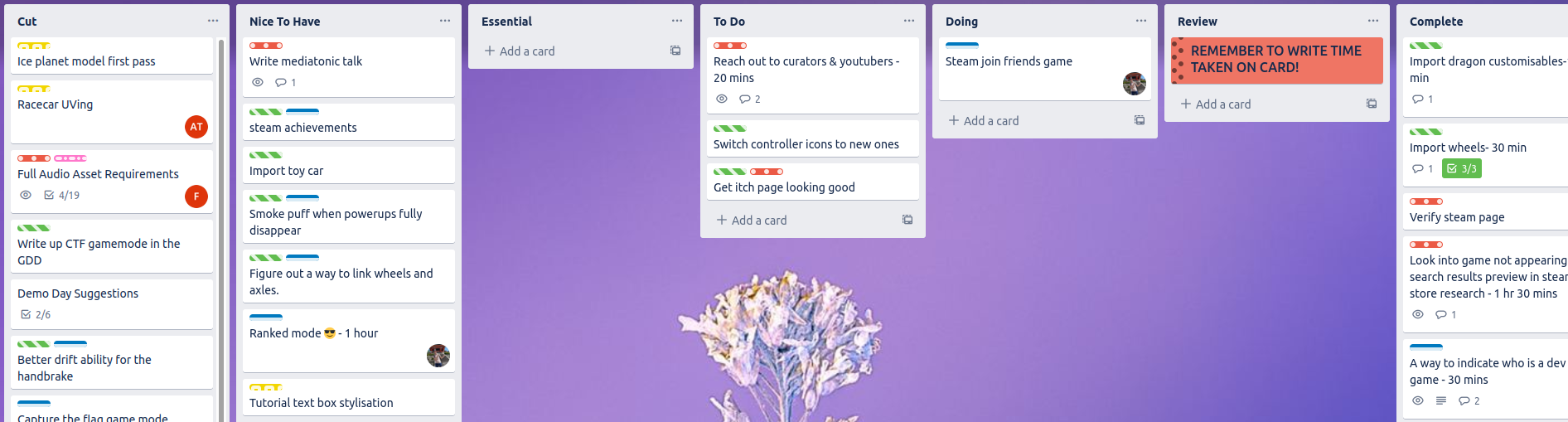

This project was definitely a challenge, but was a joy to work on. It was the second multiplayer project I’ve done, with a lot of the same development team that worked on Yvaga Station. We made use of Trello for task tracking, Git for version control, and Google Docs for documentation.

This was my first project as a dedicated producer, allowing me to commit to the role and have the time to do long term planning for the project, making sure each sprint was building towards a goal, with a clear idea of what we wanted to achieve and include. I was also able to ensure the team were prioritising mental health and ensure that the project was flexible enough to allow for this prioritisation. This was especially important as early in development we went into the countries first lock down due to Coronavirus. This flexibility was achieved in part through regular maintenance of the projects scope, giving a clear view of our end goal and making it clearer which tasks were the highest priority, helping to drive and focus our sprint goals.

Another part of this flexibility was encouraging a sense of shared ownership over assets and the game as a whole. For example, when it came to texturing models artists were encouraged to work on the highest priority assets, regardless of if they were the one who originally modelled it, allowing us to get assets into engine quicker and not be slowed down if an individuals schedule changed last minute.

The combination of these methods kept the project on a consistent path long term while remaining flexible in the short term, allowing team members to balance the project with their health and other commitments, without significantly compromising the final product.

As part of encouraging a sense of ownership, we strived to create an open environment where all members had a voice and were empowered to provide input and had agency. Although I was yet to learn the term for it, we were striving for “Creative Equity”, with every member of the team having a voice, but those with expertise or experience in the current discussion having more weight to their input. This allowed everyone to have that sense of agency, while helping to avoid some of the pitfalls of “Design by Committee”, such as ending up with an average, if bland, game.

We also implemented department leads, freeing me to focus on macro level problems, looking ahead for blockers and planning our roadmap, rather than getting bogged down in micro details that were best left to the team. This also allowed those that work best with minimal supervision to thrive, while providing support and points of contact for those who worked better with more supervision.

This was my first project working with an art department, and while it went well there were a couple of issues, resulting in frustration or work needing to be redone. The main issue was handling the production of concept art, as at the start we had no formalised way of handling reviews & sign offs on concept sheets. This led to a few instances where an asset had started being modelled before issues with it were raised. This cost us more time than if issues had been raised at concept stage, as well as frustration from the artists for needing to redo large portions of an asset, or in one case scrap an asset completely. This has been improved significantly in future projects, with submission of concept art being much more vocal, and a larger emphasis and importance being placed upon providing comprehensive, timely feedback. This has lead to less work needing to be redone, while also reducing the amount of time artists are sat around waiting for concept sheets to be signed off.

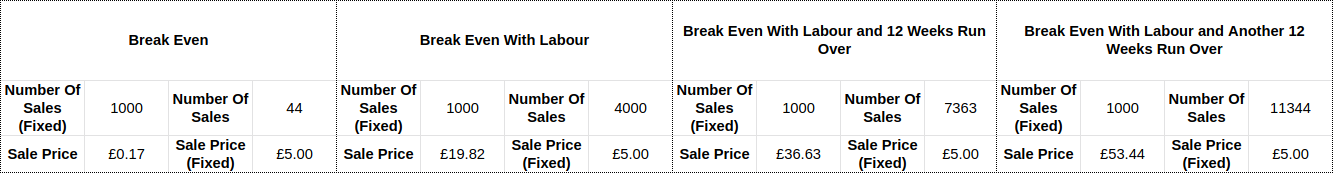

I also created a budget mock-up for the project, which can be viewed here, allowing someone to easily view the number of sales and the sale price required to break even on the project. This was easily adjusted, allowing a fixed price per unit to be set, which would then calculate the number of units we would need to sell at this price, or setting a fixed number of sales, and calculating the price we would need to sell at if we only sold that many. This allowed us to easily see if the price we wanted to sell at was feasible, given the number of sales we expected to make.

As this was a student project I included a break even for costs excluding labour, so Steam licensing fees and the fees for using PUN2, our networking solution for the project, as well as the break even including labour. I also added the calculations for break even with extra development time, allowing the cost of further development to be weighed against the value it would add to the product.